|

When the G7 finance ministers returned home following the Oct. 13 weekend meeting of the International Monetary and Finance Committee, the world’s dailies all led with the same story: substantial gains on world stock markets underpinned by a stoic photo-op of the wizards of national finance on the steps of the U.S. Treasury.

The meeting and market response fueled hope that the “coordinated bailout” had succeeded. Had the ministers eliminated the horrific specter of 1930s-style economic depression? Was financial collapse averted? Had confidence returned to refresh what John Maynard Keynes called the animal spirits1 of capitalism? Maybe not.

One month later the G20 was back in Washington trying again.

What Happened?

The rapid fallout from less than a decade of financial speculation has been mind-boggling. Barely legal, the unregulated bubble in “credit derivatives”2 grew from $1 trillion in 2003 to $15 trillion in 20073 to finally burst, leaving the global financial system on life support in the public ward.

The unraveling began in August 2007, reaching crisis levels in October 2008. The “toxic” credit bubble was pricked by the deflation in another bubble—the U.S. housing market. Bad mortgages defaulted on a large scale, raising other questions as to the viability of certain credit derivative investments. The result: an implosion of U.S. investment banking with knock-on threats to overexposed retail banks. Inter-bank credit froze due to counterparty risk, and lack of credit threatened the productive sectors of the world’s economies.

Firms began to fail for lack of credit and others were forced to sell off assets due to high indebtedness. G7 economic growth dove into the red and everyone grappled for a solution. For global investors, it was paradise lost, as millions of dollars in gains evaporated almost overnight.

The economic analysis of technical failures only partially explains what happened. Politics had created a legal framework that allowed, and even encouraged, previously illegal practices. Deregulation allowed selling-on mortgage loans to other institutions, opened the door to previously illegal financial mergers combining banks with insurance companies (e.g. Citigroup, Inc.), and even prohibited the U.S. government from adequately regulating derivatives.

Housing Bubble

Back before August 2007, economists still echoed the commonly accepted fallacy that “house prices never fall.” When the credit bubble that funded house purchases showed signs of bursting in August 2007, journalists were forced to pen a new reality.

Avoiding getting into tedious economic detail, the press instead painted a picture of the poor tricked into becoming owners of houses they could not afford. With an eye to revenue from the real estate classifieds, journalists are careful to avoid the term housing bubble as that might reflect oversupply.

Although the financial press laid the blame for the current financial pandemic on “toxic assets,” the mainstream media blames the crisis on these sub-prime mortgages—a polite term for loans to poor and unemployed borrowers.4 Journalists vilified retail mortgage lenders, portraying them as perverse car salesmen in cheap suits conning uneducated buyers for large sales commissions. Here was the bad guy that had made the healthy sophisticated financial system “toxic.” As it turns out the story is not that simple.

Only recently has former Fed chief, Alan Greenspan, been questioned for not deflating the housing bubble by raising historically low interest rates before it was too late.5 In effect, the Fed chose to turn a dot-com stock bubble into a housing bubble to prevent recession, but to do this there had to be lots of cheap credit. Instead of preventing recession, the Fed was complicit in creating a worse recession later. Maybe this is why Greenspan chose as his successor Ben Bernanke, whose Ph.D. specialization was dealing with unemployment.6

While predictable defaults on sub-prime mortgages did pull the trigger on credit derivatives, the credit derivatives story began more than a decade ago with legislative deregulation. This deregulation broke down protections created during the New Deal to protect the damaged U.S. economy from harmful financial speculation.

By revoking protective laws, special interest groups created loopholes enabling financial derivatives to become an integral part of the largest unregulated investment and insurance industries on the planet. Legislative changes enabled mergers in the insurance and investment sector, and the creation of offshore unregulated virtual banks (called Special Investment Vehicles, SIVs) onto which Wall Street could legally offload7 their risks. New laws also explicitly restricted certain key regulations on derivatives in 2000.8

Banking rules and financial regulations are there for a reason but they hamper profitability by restricting leverage. Leverage is the ability to invest money you don’t have. A regulated bank is required to maintain a mere 8% of their investments in deposits. This means they can loan out more that 12 times the money they have. This is reasonable leverage but non-banks such as hedge funds don’t even have the 8% restriction so their ability to leverage assets is even greater. By removing protective legislation, politicians contributed to global financial instability. In the meantime, a small group of “sophisticated” investors have made a lot of money.

Bad Debt

Bursting housing market bubbles, especially in the United States, raised fears that credit derivates had become toxic securities. A toxic security is a credit derivative gone bad. Describing derivatives is notoriously difficult, yet they are central to this crisis. The U.S. Treasury Office of Comptroller of the Currency Administration of National Banks reports that 99% of these are “credit default swaps” (CDSs), a technical term for unregulated insurance contracts designed to protect against institutional collapse.9

Simply put, a bank makes a loan, then offloads the loan to someone else and they take out insurance in case the system fails. Abusing the system ensures that it fails, so a call is made on the insurance, but because it is unregulated no-one has the cash to pay up. A credit default swap is a panic button that banks can punch if all goes to hell-in-a-hand-basket, a situation referred to by finance ministers as “systemic” failure. Fed Chairman Bernanke described the situation to the House Committee on the Budget as follows:

“More fundamentally, the turmoil is the aftermath of a credit boom characterized by under-pricing of risk, excessive leverage, and an increasing reliance on complex and opaque financial instruments that have proved to be fragile under stress.”10

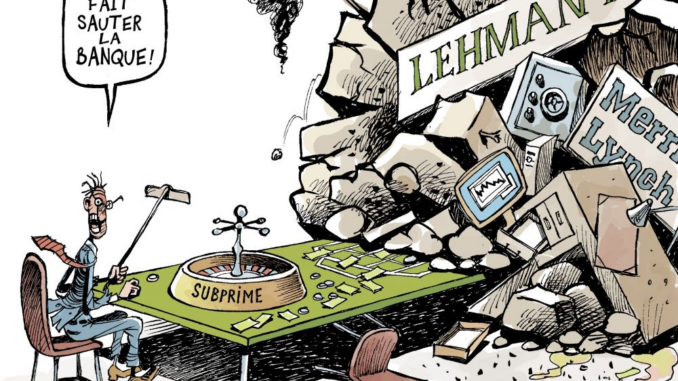

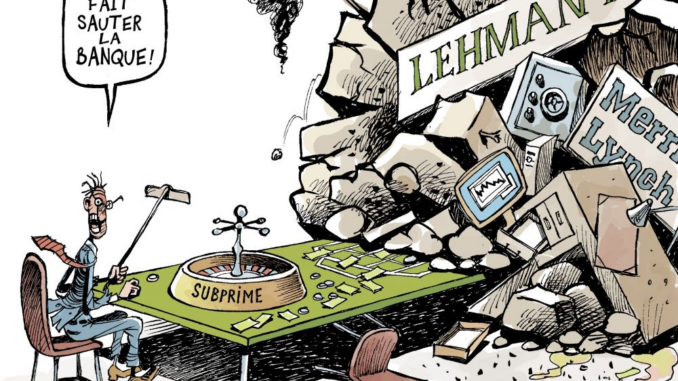

Markets play with other people’s money so governments write rules to prevent abusive excess. Banking rules require that regulated banks or insurance providers maintain sufficient assets to cover their calls. When there are no rules, maintaining just-in-case assets is an encumbrance. It is more profitable to invest them too. “Casino finance” encourages risk. Technical terms like “undercapitalized,” “overextended,” and “over-leveraged” all mean one thing—make money now and worry about the crash when it happens. You can always plead for government help, especially if you have friends in high places. It happened, and it is not over yet.

Even the regulated insurance companies got into the business of credit derivatives and despite their enormous assets they were equally impotent when the inevitable systemic failure happened. They had simply taken on too much risk. For this reason the U.S. government rescued its largest insurance company, AIG, with $123 billion in emergency taxpayer-funded loans. On Nov. 10 this loan was revised upward to $150 billion as AIG had rapidly consumed earlier federal loan facilities.11

Some credit securities have collateral. These are called Collateralized Debt Obligations12 (or CDOs13), one of many so-called structured finance products. Also known as asset-backed securities, a CDO is a mixture of repackaged loans backed by some form of asset. They are sold as an investment product to other banks, mutual funds, etc.

One common category of CDO is real estate assets. These are called mortgage-backed securities and hold houses as collateral. A house has a value equivalent to a small percentage of its defaulted mortgage, (let’s say a third for a 15- or 20-year mortgage), but when house prices drop, this fraction drops too. House buyers defaulted and returned the keys to the bank leaving a big hole in the CDO where the mortgage used to be.

A CDO is created from many different assets (even other CDOs). This makes it hard for buyers to know what is really in them. Opacity caused fear and this fear pulled the trigger that caused a collapse of the credit derivatives market. The fear spread to various other markets, bringing down the whole house of cards.

Globalizing the problem, investment banks packaged up and sold off CDOs to the highest bidder with the help of complicit ratings agencies that granted them a highly secure (AAA, Aaa) rating. Then the investment banks that generated and held CDOs began to fail. The retail banks reported losses. The inter-bank credit markets froze because no-one trusted the borrower to repay. This caused a crisis of illiquidity that all but toppled the banking industry. Financial stocks collapsed as firms failed, and this percolated through the stock markets.

Then the “real” economy became caught up in the collapse as corporations found it impossible to refinance their loans and letters of credit were looked on with greater suspicion. This has in turn led to crises such as General Motors, etc. Recently this has also caused newspapers to collapse due to lack of advertising funds and massive layoffs.

As far back as 2005, then-New York Attorney General Eliot Spitzer began to investigate CDOs in the respected (now deceased) investment bank, Bear Stearns. Matthew Sterns in an article for TheStreet.com wrote:

“[…] Spitzer’s office is looking into the marketing of three CDOs sold to Hudson United [Bank] and the valuations provided to the bank on those transactions … The great thing about CDOs is that just about anything that produces revenue can be stuffed into the underlying portfolio that backs these securities. A typical CDO represents claims on cash flow from a combination of junk bonds, bank loans, accounts receivable, mortgage-backed securities—even other CDOs. […] But cynics say the CDO structure provides a perfect vehicle for banks and other companies to dump their poor-performing loans and bonds on unsuspecting investors.”14

CDOs became standard fare for the growing hedge fund industry and spurred the boom in private capital firms that use their leverage in their merger and acquisition activities. The financial technique of “hedging” is important from an investment perspective but modern hedge funds have less to do with hedging and much more to do with what John Kenneth Galbraith called “innocent fraud.” John Kay, columnist for the Financial Times, defines this as “[a] process that systematically benefits one group at the expense of another but generally falls short of outright criminality.”15

The hedge funds have been fabricating “value” on a very grand scale. They have invented “financial instruments” willy-nilly since the 1980s, completely free from market regulation both off- and on-shore. In layman’s terminology, financial instruments fabricate value from hidden parts of little or no value. Gillian Tett, in a 2006 investigation for the Financial Times asked prescient questions:

“[…] the whole credit derivatives world has exploded at such a dizzy pace that nobody is exactly sure where the loan risk has gone. Have all the investors who have bought credit derivatives contracts checked the fine print to see what losses they could sustain? Does anybody understand the chain reaction that might be triggered by such losses? Could the world’s trading systems cope? And what would happen to all those hedge funds that have been jumping into the credit derivatives world?”16

Trillions of speculative dollars now control markets. Numbers in trillions are difficult to fathom. However, the gravity of the situation is evidenced by two salient facts. First, there are no more independent investment banks on Wall Street. None survived the massive wealth creation and elimination that was the credit derivatives bubble. They have all gone bust and have been rescued by the U.S. government, and/or bought out.

The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has allowed the smartest of the investment banks (such as Morgan Stanley, whose “dream team” invented credit derivatives, and Goldman Sachs, whose CEO Hank Paulson moved over to Treasury in 2006), to transform themselves into “bank holding companies” with vital life support systems offered by the U.S. government to prevent them from going under.17 Even insurance companies are buying up small banks with the hope that they too can do the same.

Second, the planetary unregulated derivatives markets now have a nominal value larger than all the world’s stock markets combined.

Who Will Pay the Price?

In the 2008 Global Financial Stability Report,18 Jaime Caruana, the councilor and director of the Monetary and Capital Markets Department of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) said: “There is now an acute awareness of the fragility of confidence in financial institutions and markets. The global financial system is going through a process of de-leveraging …”

De-leveraging means losing money. This loss in value means that banks have a hard time finding assets (such as deposits) to get back to a minimal 8% of the nominal value of their complex debt portfolio. There are two ways to do this as the toxic assets are being written off: either get more money in, as deposits for example, or write off the debt obligations that will never be paid. In short, the bubble needs to burst; the question is if it will deflate gradually or be a blowout.

If orderly deflation is possible through massive intervention and global coordination (even including tax havens), it may be possible to prevent an implosion of the banking system. If not, the world will not end in a bang but huge write-downs will lead to a drastic shrinking of the financial system and major consequences on a global scale.

One way or another, the financial innovations that led to the crisis must be controlled or shut down. These investments are not available to the poor. They made some very rich individuals much richer.

As they crash, who should pay the price? The G20 meeting called by outgoing President Bush began to reformulate the global financial system. Current bailout plans, fueled by taxpayer money, are being re-designed behind closed doors to ensure public losses and private gains.

Former Portuguese President Mario Soares recently pointed out the paradoxical nature of privatizing water, energy, and government, but using taxpayer’s money to bail out the banking sector. He demanded stringent punishment and called to “put those [bankers] responsible in jail for their fraudulent collapse.”19

In a debate published in the UK Economist magazine, Joseph E. Stiglitz argued that regulation should be tightened after the correction but he was not hopeful:

“… anyone who has seen America’s political processes at work knows that after Wall Street gets its money, it will begin fighting the regulations. It will say: ‘government must be careful not to overreact; we have to maintain the financial markets’ creativity.’ The fact of the matter is that most of that creativity was directed to circumventing regulations and regulatory arbitrage, creative accounting so no-one, not even the banks, knew their financial position …”20

As Martin Wolfe, chief economics commentator for the Financial Times of London, puts it: “I would say that the financial industry cannot continue to run in its present form. There is vastly too much privatization of profit and socialization of losses to be tolerable. There are obviously huge weaknesses in the existing regulatory framework.”21

Regulation or Accommodation?

The global financial system is grievously ill. In early October 2008 the financial sector known as investment banking followed venerable firms (like Bear Sterns with more than 100 years of history in investment banking), and simply ceased to exist. With the demise of Wall Street investment banks, the question is: are we seeing the death of finance as we have come to know it, or is this another periodic shake-up that will leave a renewed cast of players in the same old system?

When the global credit system began to fall apart, world leaders knew they were confronting a major crisis. They sent out a call for coordinated action and began a series of frantic meetings all over the world culminating in the G20 meeting in Washington on the weekend of Nov. 15.

The first challenge was to get taxpayers to foot the bill to save the companies that created the mess. The problem was, no-one really had a clear idea of how the money should be spent, what the priorities should be, or what a real solution would look like. While President Bush pushed a straight free-trade, more-of-the-same line, European leaders called for global regulation, which Bush rejected. Then there was the core question: How much could a workable global financial bailout really cost and what will the taxpayers get for their money?

The profit to be made in unregulated credit derivatives made them attractive. However, their complexity and opacity led Warren Buffett to label them “financial weapons of mass destruction.”22 Who built these weapons? To answer that question one has to look behind the legislation that deregulated certain types of derivative investments.

Key deregulation legislation included the Commodity Futures Modernization Act of 2000,23 which allowed the people who sell mortgages to distance themselves from the ultimate collectors. This enabled the CDO market, for example. Also important was the 1999 Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act, which partially repealed the Glass-Steagal Act, passed in 1933 as a response to the financial excesses that led to the 1929 Wall Street crash. Glass-Steagal established the FDIC in an attempt to restore confidence in the U.S. banking industry after the great depression.

Senator Phil Gramm, chairman of the Senate Finance Banking Committee and co-sponsor of the 1999 Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act to repeal these New Deal protections, exemplifies the conflict of public-private interests that hold sway in U.S. government. As Eric Lipton and Stephen Labaton note in their New York Times article,24 for the Gramm’s deregulation was a family business:

“While the Commodity Futures Trading Commission—under the leadership of Mr. Gramm’s wife, Wendy—had approved rules in 1989 and 1993 exempting some swaps and derivatives from regulation, there was still concern that that step was not enough. In December 2000, the Commodity Futures Modernization Act was passed as part of a larger bill by unanimous consent after Mr. Gramm dominated the Senate debate.”

Senator Gramm is a master of revolving doors. This retired career politician was Senator for the state of Texas for 24 years (both Democratic and Republican). A Doctor of Economics, Gramm is directly responsible for both of the above pieces of legislation. He is now “business group vice chairman25” (a lobbying position) for Switzerland’s largest bank, the Union Bank of Switzerland (UBS).

Despite the crisis, don’t expect world leaders to finally take the bull by its horns. Many of the powerful individuals acting as the architects of the U.S. and European bailout plans move constantly through that same revolving door between elite private finance positions and national finance ministries. Chuck Grassley, the most senior Republican in the U.S. Senate Finance Committee, recently called for an investigation into the objectivity of advisers in the U.S. treasury (all of whom are former Goldman Sachs employees), stopping just short of demanding an investigation into current U.S. Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson, formerly the head of Goldman Sachs.26

To the “Rescue”

On Oct. 13, the U.S. government announced the largest-ever investment of U.S. public money (over $700 billion) in the private financial industry. That day Wall Street celebrated and the S&P 500 had its largest one-day rise since the 1930s depression. Tuesday did not go so well. Wednesday, the U.S. Treasury began pumping $250 billion into the banking sector, however the S&P 500 had its worst one-day fall27 since Black Monday in 1987.

In the United States, reaching the agreement on the emergency aid wasn’t easy. The menus offered to the House and Senate differed. Although they had the same price tag—about $700 billion—the ingredients varied. Surprisingly the first menu offered was rejected on Sept. 29, but the aptly named TARP (Troubled Asset Relief Program28) passed in the house on Oct. 3 and was hastily signed into law. The TARP was similar to the plan rejected earlier that week. Stirring in a few billion dollars of pork29 before the election made the second offer more digestible to state representatives. President-elect Obama voted “yea”30 although public opinion surveys show that the majority of the U.S. population disapproves of the bailout package.

The rest of October saw stock markets thrash across the world, with the highest volatility measures on record. The Chicago Board of Options Exchange keeps an index of the near-term volatility of the S&P 500 called the VIX. The VIX has hovered around 15% for the past few decades; it touched an all-time high of 80% that week, the next week it almost reached 90%,31 and stayed above 60% through the first weeks of November.

The most active trading was in the markets that trade the markets, (the derivatives markets), managed by hedge funds and what is left of the investment-banking sector. Hedged positions unraveled resulting in massive sell-offs. Some hedge funds have gone belly-up, others are essentially insolvent, and a few stopped trading, citing the unpredictability of the market. Those that still have enough leverage to move markets have been making fortunes in periods of extreme volatility leading to questionable behavior. Suspected illegal trading is being investigated. The Porsche buy-out of Volkswagen is one such example. As the stock markets convulsed violently, the credit markets eyed up the massive new flows of taxpayer cash with cautious optimism and an eye to their shareholders’ bottom line.

Meanwhile on the global stage, the leaders of the G7 of some of the world’s largest financial economies met on Oct. 11 to hash out a coordinated attempt to stem financial collapse. For much the same reasons, the next day the G7 (and non-G7) Europeans were again meeting in Brussels. Meetings continued throughout the world in regional blocks until, on Nov. 15, the G20 met in Washington, DC.

Hasty negotiations have been taking place across the planet as politicians are informed that they have little choice but to agree to bail out the global banking sector. As world leaders turn to the cameras explaining in somber tones that throwing trillions of dollars of tax funds into the world’s frozen financial credit system will thaw it sufficiently to prevent the dreaded disorderly unwinding, it is obvious that few have the faintest idea how these incredibly costly plans will work out, if indeed they do.

Leaders in the economically neoclassical European Union have assiduously avoided using the term “nationalize” when speaking of injection of public funds into the global banking system. That said, in Europe alone, the equivalent of nearly €2 trillion (Euros) in national taxpayer funds are being fed to starved national credit markets in a hope that this will nourish them back to health. The question is what public investors will get for their money.

Earlier this year the IMF was selling off its gold reserves to pay its bills. Its portfolio of debts has been dwindling in recent years. In fact, Turkey was its one remaining large client. Developing nations began rejecting its conditions, paying off their debt, and looking elsewhere for financing. The crisis offers the IMF a chance to once again take center stage. The IMF is trying to rescue the Ukrainian, Hungarian, and Icelandic economies with massive loans32 and pushing new loans on Mexico and other nations as well.

Proposals for new roles for the IMF and the World Bank were at the center of the discussions at the G20 meeting. The declaration33 emphasized the IMF sister organization the Financial Stability Forum (FSF) and called for recapitalizing the IMF:

“We stress the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) important role in crisis response, welcome its new short-term liquidity facility, and urge the ongoing review of its instruments and facilities to ensure flexibility […] and we welcome the recent introduction of new facilities by the World Bank in the areas of infrastructure and trade finance.”

It had this to say on the FSF:

“The Financial Stability Forum (FSF) must expand urgently to a broader membership of emerging economies, and other major standard setting bodies should promptly review their membership. The IMF, in collaboration with the expanded FSF and other bodies, should work to better identify vulnerabilities, anticipate potential stresses, and act swiftly to play a key role in crisis response.”

Wall Street Woes

Back in the highly leveraged world of Wall Street, the situation is looking grim. The Federal Reserve is desperately trying to deal with a toxic mix of bursting bubbles. Apparently grasping at straws, the U.S. government has made various abrupt policy about-turns. Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson34 originally planned to buy up the toxic securities from the banks that hold them as public “assets,” thereby attacking the problem at its source. Then Paulson changed his mind and went for the lubrication option of injecting tax money as liquidity directly into the banking system.

Anna Schwartz, who co-authored A Monetary History of the United States (1963) with Milton Friedman, was interviewed by the Wall Street Journal.35 Schwartz considers that lubricating the credit markets with public money isn’t working because it does not deal with the problem at hand: “This is not due to a lack of money available to lend […] but to a lack of faith in the ability of borrowers to repay their debts.” “The Fed,” she argues, “has gone about as if the problem is a shortage of liquidity. That is not the basic problem. The basic problem for the markets is […] [uncertainty] that the balance sheets of financial firms are credible.”

Analysts warned36 that the decision not to buy troubled assets would have a negative impact on the market. Indeed, the ABX valuation of sub-prime mortgages at 50 cents on the dollar dropped to 32 cents in September.

It may now be too late to return to the original idea of buying the toxic securities with tax money, as they have so little value the banks would still remain undercapitalized even if the government paid the correct price for them to get them off the market. It can be argued that if this is true then the system is bound to fail because the leveraging cannot be de-leveraged quickly enough. So, the question remains: why even go ahead with this bailout?

Injecting public funds into an ailing global financial system is like throwing spaghetti to the wall. If it sticks, the chefs congratulate each other over the successful recipe. If this coordinated bailout sticks, presumably, the financial system will hold together long enough to unwind in an orderly fashion. This will mean losses without collapse. However, unwind it must. Behind the scenes, the regulation agencies and the FBI will be forced to spank the wrists of a few derivatives traders and investment bankers, while bank shareholders are quietly rescued by government charity programs.

What happens if the spaghetti fails to stick? Might it be necessary that a few more hundreds of billions of dollars in taxpayer cash could be required to keep the corporate ATM machines functioning? Would further nationalization work? If so, for whom? The falls in the stock markets, especially in financial stocks, are a reaction to the fact that financial investment and refinancing groups (some very private in nature) have overreached themselves. Stock market drops are a symptom of ill-health on a much larger scale, and trading in derivatives markets is much larger than stock market trading, or at least it used to be. No one really knows if injection of public funds will solve anything. From the perspective of the stock market, Monday Oct. 13 might have been a dead cat bounce37 on a grand scale.

So What Next?

If the global financial system must be reformed to prevent failure, who will be invited to design the new architecture to replace it? President Bush convened the Nov. 15 meeting of the G20 to hand-pick the nations and international institutions allowed to participate and control the terms of negotiation.

After downplaying expectations, it was no surprise that the summit produced a document with 10 pages of vague declarations and negated concrete measures for global controls suggested by the European Commission.

Meanwhile others are proposing real alternatives. Former Vice President Gore is the flag-bearer for Green Keynesianism to save both the economy and the environment. In a student video to “get out the vote” for President-elect Obama, he said:

“The financial crisis, the economic crisis, is the perfect time to make the investments that are necessary investments to transform [the U.S.] energy infrastructure. […] The economic crisis and the climate crisis not only have the same causes, they have the same solutions.”38

It will be President-elect Obama who will lead much of the redesign/recovery process. Obama did not attend the Nov. 15 summit but sent representatives to report back to him.

None of the language in the White House G20 Summit Declaration39 is truly innovative. In contrast to Obama’s promises of change, the Bush G20 declaration rehashes the conventional wisdom that has crippled the world financial system. Proposals include further deregulation of financial and trade markets, explicit prohibitions on protectionism, or restrictions on private capital flows. Along with prudential oversight of market operations, the G20 leaders signed on to resolving the moribund Doha round of the WTO within a year.

Proposals such as the “New Principles and Rules to Build an Economic System that Works for People and the Planet” demanded by certain social movements40 seem to have been ignored. Perhaps it is understandable at this early stage that details are absent, but it would be interesting to know whether the “harmonization of global accounting standards” would preclude tax avoidance techniques such as transfer pricing.

Obama’s new team includes many of the same faces that oversaw this deregulation scam in the first place, including Robert Rubin of CitiGroup who was on Clinton’s team. If Obama chooses to follow Bush’s blueprint there will be little change in the world financial system. Instead, the system will get a quick tune-up and this investment vehicle will get right back on the road. Whatever happens, let’s hope the architects of the global financial system realize that it is not too big to fail.

End Notes

- http://www.economist.com/research/Economics/alphabetic.cfm?letter=A#animalspirits.

- Credit derivatives are so new that they were first reported by U.S. regulating agency (the OCC) in 1997.

- http://occ.treas.gov/ftp/release/2008-65b.pdf; The OCC’s Quarterly Report on Bank Trading and Derivatives Activities Second Quarter 2008: U.S. derivatives market has a nominal vale of more than $182 trillion; of these 15 trillion are credit derivatives. Credit derivatives were first reported in Q1 1997 when there were 55Bn. By Q3 2003 they had reached one trillion. Since then the bubble expanded on average 100% every year until 2007 when it started to burst ($2.3Tn. 2004, $5.8Tn. 2005 $9.0Tn. 2006, $15.9Tn. 2007).

- Though sub-prime is a U.S. term, many other countries weakened their protections in mortgage lending practices thus poisoning their credit markets too, with unpayable debt.

- For more information on Greenspan’s strategy see Jonathan Ford’s article on the city’s relentless expansion: FT.com, Nov 15th: http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/ea2c445c-b059-11dd-a795-0000779fd18c.html.

- Ben Bernanke’s PhD thesis can be found here: http://dspace.mit.edu/handle/1721.1/29839.

- In financial terms “offloading” is to rid oneself of something by selling it or passing it on to someone/thing else.

- http://www.texasobserver.org/article.php?aid=2767.

- On a “60 Minutes” show earlier this month, former staff member of the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, Michael Greenberger, described a credit swap in brief: “A credit default swap is a contract between two people, one of whom is giving insurance to the other that he will be paid in the event that a financial institution, or a financial instrument, fails. It is an insurance contract, but they’ve [those financial geniuses responsible for inventing the credit default swaps such as J.P. Morgan’s dream team] been very careful not to call it that because if it were insurance, it would be regulated. So they use a magic substitute word called a ‘swap,’ which by virtue of federal law is deregulated.”

- Chairman Ben S. Bernanke, Economic Outlook and Financial Markets, FRB testimony before the Committee on the Budget, U.S. House of Representatives, October 20, 2008: http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/testimony/bernanke20081020a.htm.

- Board of governors of the Federal Reserve press release: http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/other/20081110a.htm.

- Also known as asset-backed commercial paper.

- Or CDOs of CDOs commonly referred to as CDO.

- “Bear Stearns Shakes the CDO Honey Pot”; Matthew Goldstein:

http://www.thestreet.com/_tscana/markets/matthewgoldstein/10236829.html.

- “Banks Got Burned by Their Own Fraud”; John Kay, Financial Times, Oct. 14th: http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/12ade22e-99fc-11dd-960e-000077b07658.html.

- http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/7886e2a8-b967-11da-9d02-0000779e2340.html.

- http://topics.nytimes.com/top/news/business/companies/goldman_sachs_group_inc/index.html.

- World Economic and Financial Surveys: Global Financial Stability Report: Financial Stress and De-leveraging Macro-Financial Implications and Policy, October 2008: http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/gfsr/2008/02/index.htm.

- “Meter en la cárcel a los grandes responsables de las quiebras fraudulentas”: http://democraciadigital.navegalo.com/articulos/index.php?id=144.

- Economist debate, Con: Joseph E. Stiglitz: “Would it be a mistake to regulate the economic crisis heavily after the crisis?” http://www.economist.com/debate/index.cfm?debate_id=14&action=hall.

- Comment on economist’s forum: Martin Wolfe (associate editor and chief economics commentator at the Financial Times, London), http://blogs.ft.com/wolfforum/2008/10/globalisation-is-not-our-enemy/.

- “Weapons of Mass Financial Destruction,” Le Monde Diplomatique, Gabriel Koldo: http://mondediplo.com/2006/10/02finance.

- CFMA, H.R. 5660 and S.3283.

- “The Reckoning, Deregulator Looks Back, Unswayed,” Eric Lipton and Stephen Labaton; Nov. 16: http://www.nytimes.com/2008/11/17/business/economy/17gramm.html.

- http://www.ubs.com/1/e/investors/boards/seniorleadership/vicechairmen.html.

- Stephanie Kirchgaessner: “Call for Probe into Ex-Goldman Executives,” Financial Times of London, Nov 17th: http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/47bf32f0-b447-11dd-8e35-0000779fd18c.html.

- Measured in percentage terms.

- http://abcnews.go.com/Business/Economy/story?id=5932586.

- Various riders were added to the $700bn. TARP bill in order to win back votes for the measure, which is the largest single U.S. government expenditure in history. Republican House Representative Spencer Bachus was quoted in the New York Times as saying: “The bill that came over from the Senate includes a series of pork-barrel projects that are simply unacceptable not only to me, but to the American people …”, http://dealbook.blogs.nytimes.com/2008/10/03/house-to-vote-on-rescue-proposal/.

- (Yea, 74, Nay 25, Not voting, Sen. Kennedy, 1) http://www.senate.gov/legislative/LIS/roll_call_lists/roll_call_vote_cfm.cfm?congress=110&session=2&vote=00213.

- http://www.bigcharts.com/custom/cboe-com/cboe.asp?symb=vix&time=8&uf=0&draw.x=0&draw.y=0.

- (Hungary €12.3 Bn., Ukraine $16.4 Bn., Iceland $2.1Bn.) http://www.imf.org/external/news/.

- Declaration of the Summit of Financial Markets and the World Economy: http://www.whitehouse.gov/news/releases/2008/11/print/20081115-1.html.

- http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/1a0b47a8-880b-11dd-b114-0000779fd18c.html.

- The Weekend Interview, Oct. 18, 2008, Anna Schwartz, Bernanke Is Fighting the Last War: Everything Works Much Better When Wrong Decisions are Punished and Good Decisions Make You Rich, By Brian M. Carney, Wall St. Journal: http://online.wsj.com/article/SB122428279231046053.html.

- http://www.ft.com/cms/bfba2c48-5588-11dc-b971-0000779fd2ac.html.

- Definition: Dead Cat Bounce: http://www.phrases.org.uk/meanings/108600.html.

- Former Vice President of the United States Al Gore on studio video for students to get out the vote: http://www.wecansolveit.org/content/al-gore-powervote-webcast.

- http://www.whitehouse.gov/news/releases/2008/11/print/20081115-1.html.

- http://www.choike.org/bw2/#english2.

Tony Phillips is a researcher and journalist on trade and multinational finance with an emphasis on dictatorships and the WTO, and a translator and analyst for the Americas Program at www.americaspolicy.org. Much of Tony’s work is published at https://projectallende.org/.

|

Tony,

I see you’re taking a well deserved break, as no recent posts received. Happy New Year to you, hope graduation goes well and congratulations on the publishing…

Just to let you know, two Irish Guys currently taking part in tha Dakar Rally. They finish 18th January in Buenos Aires. Link to their blog at http://www.teamdakarireland.com/

Best of luck in 2009

Ruth and Lily