In Latin America, oil and water don’t mix. Or do they?

Latin American neighbors, Argentina and Bolivia have recently undertaken a re-nationalizing of their natural resources each their own way and for different reasons. This article compares the public-private struggles for oil and water resources in Argentina and in Bolivia.

Re-nationalization is one option to reverse the IMF-enforced privatization of public resources that happened in the 1990’s. The modus operandum for the New York-based lords of international finance, was to place huge, (and often corrupt) pressure on indebted governments to hand over the family jewels into the hands of friendly private corporations. The price paid was then required of the governments in order to partially repay their debts to the IMF, and their friends, the investment bankers downtown. It was a harsh but profitable formula and its use may be the reason that Argentina and Brazil are both in the process of canceling and/or paying back their debt to the IMF at record rates. What the IMF will do with 49% of its recent portfolio soon to be repaid and no more large Latin American customers is speculation for another article.

One such sale took place in Argentina in 1993 when “Aguas Argentinas” was privatized along with 90% of the state enterprises, and a 30-year contract to operate municipal water supplies was put out to bid. Various European water companies bought in, a controlling share going to French corporation Suez and its partially owned Spanish subsidiary “Aguas de Barcelona“. British Anglian Water, and Italian Vivendi along with various Spanish banks took smaller shares as well.

Things did not go well with the privatized Aguas Argentinas. The Europeans saw their profit fall when the Argentine government broke with the dollar peg and continued to impose government regulations to prevent water cost increases for their impoverished citizens and reeling industries. Many sources have been quoted from earlier this year asserting that Suez and the other Aguas Argentinas shareholders never intended to renew their 2006 concession to operate Buenos Aires water supplies. If this is in fact true, the Argentine government’s nationalization move may be viewed with relief by Suez et al. It does enable them to pursue a lawsuit to recoup in their investments however unlikely it may be that this will be repaid. This is Argentina, and the government is quite adept at re-nationalization while avoid onerous costs in so doing.

The French government is backing Suez’s law suit relating to its 39.9% stake in Aguas Argentinas. Suez has filed a USD$1.7Bn. compensation suit with the World Bank’s International Center for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID). The suit cites water rates frozen since 2002 and claims a full refund of Suez’s claimed investment costs in Aguas Argentinas. French Foreign Ministry spokesman Jean-Baptiste Mattei was quoted as saying: “We naturally hope that this decision will be accompanied by appropriate measures to allow the company to put an end to its activities under satisfactory conditions.” Earlier this year Suez was considering a USD$350Mn. payment from an Argentine private company, accepting the $350Mn. would imply dropping the larger suit. The bid fell through, as the local company could not pay all at once. Suez, it seems, did not like their plan to pay the 350Mn. in installments.

Suez’s investments are under scrutiny by the Kirchner government. They points to 15 years of under-funding by Suez in their investment in Aguas Argentinas. The government ended the Suez et al. concession, not directly because of such under-funding, but due to high levels of nitrates in the Buenos Aires water supply, grounds for breach of contract.

Kirchner’s government has created a new company, AYSA, which has already taken over the running of Aguas Argentinas in Buenos Aires. It is 90% owned by the state and 10% by staff. The workers are represented by Jose Luis Lingeri, newly appointed director of AYSA and general secretary of the national sanitary workers union (Fentos). The board includes a mayor of Tigre, and is headed up by the pre-privatization former Chairman. Kirchner has seeded the AYSA with 180Bn. Argentine pesos to just to get them started. The creation of AYSA mirrors similar takeover tactics in the southern state of Santa Fe and Cordoba in what looks to be a somewhat coordinated national campaign.

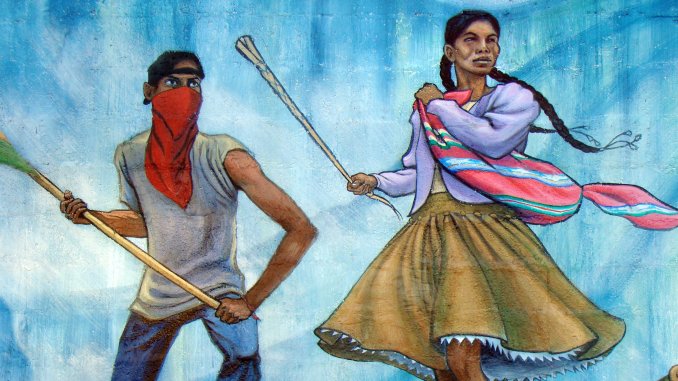

Looking northwest, Bolivia too has had mammoth struggles against privatized water. That has lead some to describe Bolivia as Latin America’s first post neo-liberal state. Suez was also involved with US corporation Bechtel in the ownership of Bolivia’s Cochabamba water resources, and those of Bolivia’s capital city; La Paz and sister city El Alto. Both Cochabamba’s and La Paz’s water supplies were returned to local control by populist action. In the case of La Paz, Suez is still seeking compensation for Aguas Illimani. The Cochabamba case however is settled. Bechtel and Suez accepted a one dollar token settlement, when their PR departments suggested that they should.

So much for water, now let’s take a quick look at oil, that other precious liquid. Ironically the number one and two private petroleum companies exploiting Bolivia’s oil and gas reserves are Argentine and Brazilian. When Bolivian national oil company, YPFB, was privatized, it was its neighbour’s own state companies that bought the largest concessions. YPF of Argentina, (now on sale by Spanish oil giant Repsol), and Brazil’s Petrobras (still nationally owned) are the largest operators in Bolivia. Repsol-YPF has large exposure to last month’s statements by President Morales relating to the re-nationalization of oil and gas operations in Bolivia. Repsol’s shares dropped considerably when the results showed that Evo had become the country’s first Aymaran indigenous President as he is known to be less corporate friendly than his recent successors.

In a parallel, and somewhat hypocritical, turn of events, the Spanish government is doing its best to resist intense pressure from its even more neoliberal neighbors. The governments and corporations of France, Germany, and Great Britain are applying pressure via the European Commission to force the Spanish government to allow open bids for the takeover of Spain’s largest electricity generator Endesa. Spain argues that such nationally-sensitive strategic resources should be protected. Endesa is up for sale and the European commission has declared illegal Spain’s insistence that the buyer of Endesa must accept a golden share arrangement to protect national interests in Endesa. A recent study has shown that such golden share arrangements are not uncommon, 141 corporations in 15 European countries have such arrangements.

Make that 140.

The European Commission has decided that using a golden share to prevent mergers in the case of Endesa is illegal and has censured Spain for attempting to use the procedure. The Spanish government may have side-stepped the issue nicely, retracting claims for golden share control, and instead handing over similar powers to the national energy regulator (CNE).

This too is considered by some to be too protectionist and there may still be some legal issues too. Brussels is yet to take a decision over the enhanced CNE protective powers. Commission sources have noted that the justification given by Spain makes use of arguments that Brussels has rejected on other occasions.

One Golden Share anomaly cited in the European Commission study was Repsol-YPF. The Argentine government holds a golden-share in Repsol-YPF. It has proven an important weapon for Argentine President Nestor Kirchner as it gives him presence on the board and a degree of strategic control especially, as is the case right now, when Repsol is interested in getting out of YPF. Golden shares are special shares, (typically only one), which give the holder, (usually a government), a say (or veto vote) in certain activities, such as mergers and acquisitions. They’re typically put in place by the government, when a once national interest is privatized. The golden share clause was added by former president Carlos Menem’s government when Repsol bought YPF.

Though it may not be the case in Europe, in Latin America it still legal for a government to ensure that its national priorities are protected. So, if it’s good for the goose then why not for the gander? Could it be that Spain has learned a profitable lesson from its former colony? Maybe Spain’s experiences in Latin America have taught them that the loss of control over critical resources (such as the largest national electricity company) to foreign private corporations may not be in the national interest? The bids are in and the German company E.ON AG’s is currently offering the highest price. It has made an all-cash offer for Endesa of 27.50 euro per share. Brussels will decide whether the CNE can adjudicate over this merger.

While some, (most importantly the Argentine voters themselves) may have lauded President Kirchner for his attempts to wrest control of strategic resources back from the foreign private sector. It remains to be said that the situation in Argentina is unusual, in that both Suez and Repsol were pulling out of Argentina anyway. It is difficult to know which came first the chicken or the egg? Is re-nationalization a result of the pull-out, or part of the reason they chose to pull out in the first place? More likely, neither is true. Repsol, like Suez, do business when profits are to be made, and once that situation changes they try to sell out while there is still something to sell.

In the case of the Argentine water business, price controls made the concession less profitable than the owners would have liked, so the Argentine government had already exerted leverage. In the case of Repsol-YPF, the rapidly depleted Argentine reserves combined with the threat to nationalize exploitation in Bolivia made Repsol’s investment in YPF very much less attractive. The oil business is an expensive one especially when it is necessary to replace expired wells by field exploration. Investments of the order of 10 years are typical before a profit can be recouped, so Repsol did what any private corporation would have done, they took what they could get as quickly as they could get it and reduced expenditure on exploration for the future. The Argentine government did not require them to do otherwise.

Repsol took a short-term approach to exploitation and maximized profits by exporting as much oil as possible. While this approach is appropriate to the profit motive but hardly appropriate to the long-term strategy for Argentine oil independence. Repsol has extracted, and most importantly, exported, the lion’s share of Argentina’s known oil reserves. So now it’s time to go. It is sensible to leave while there is still something to sell. The situation with Suez and partners is analogous, there is no future in public water in Argentina either.

The Spanish government has instructed Repsol to enter into negotiations with the Argentine government on the terms of the possible sale of YPF back to the Argentine people. Repsol has now admitted that there is little more than a decades worth of reserves in Argentina at current extraction rates. It holds less that 50% of that. Petroleum extraction costs increase as resources get scarcer which in turn leads to reduced margins. Even with the likelihood of future rises in the price of the barrel of oil, long-term profitability is unlikely and strewn with risk, not least the risk of enforced nationalization.

Government statistics regarding Argentine reserves levels, extraction volume, and oil exports, reveal that while costly exploration in Argentina has been reduced by Repsol-YPF since Repsol took over, the export of the dwindling petroleum reserves of Argentina has seen explosive growth. Between the years 1989 and 2004, oil extraction has gone up by just 51%. In the same period, lucrative exports have increased nearly 1,400%! They now account for one fifth of Argentina’s national exports by value. This has been good for the Argentine balance of payments and it probably didn’t hurt the economy of Kirchner’s home state which is rich in oil deposits, but it is bad for Argentina in the long run as she will face extremely expensive and difficult to get oil imports in the future. Maybe the Argentine government is not entirely to blame for this situation. Up until last year, the situation in Argentina did not seem so bad. Unfortunately, Repsol had been cooking the books to make things look better than they were.

Repsol is currently the subject of class action lawsuit in the state of New York, by shareholders in Repsol ADRs listed on the NYSE. The suit results from a write-down, by Repsol, of their stated global oil and gas reserves amounting to a whopping 25%! These write downs were approximately double that figure for the Repsol’s restated reserves in Argentina. That means Repsol now says it has half the reserves remaining for extraction in Argentine of that which they claimed last year, this implies that last year’s numbers were not kosher! In New York that means the shareholders are angry because of losses in investments, in Argentina this could be considered a disaster.

Comparing the Argentine situation with that of Argentina’s neighbor Bolivia we see some similarities and some differences. In Bolivia, we find many of the same companies but they face different conditions. In comparison with Argentina’s world-class sweet water reserves, those of Bolivia are small and mainly appropriate to the national market. The oil and gas business in Bolivia on the other hand is booming and production has yet to peak.

Repsol-YPF Bolivia has huge exposure to President Morales stated aims to re-nationalize the oil and gas industry. Repsol’s exit strategies are limited. It is thought that Repsol might be interested in selling it’s Bolivian operations bundled with its Argentina operations, they are physically connected by huge gas ducts so this would make sense.

With the Argentine government’s golden share control over Repsol’s market, the Argentina government itself becomes YPF’s most likely buyer. Unless Kirchner can work with Morales on the YPF interests in Bolivia there may not be much for him to buy from Repsol. Since Bolivia provides much needed supplementary gas supply to Argentina, this might present an attractive bundled offer to President Kirchner. Let’s face it, who else might be crazy enough to invest in a market that might be about to cease to be?

Water and oil are big issues still in South America. As Europe continues to privatize its critical services, South American nationalism is dragging this procedure into reverse. The coming months will reveal the privatization and nationalization futures in both Europe and South America.